1970s Redux? Is the world staring at stagflation?

June 30, 2022

“History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme,” said Mark Twain, the famous American writer.

The 1970s saw the Arab oil embargo trigger a decade-long period of double-digit rate inflation even as economic growth across different parts of the world stagnated, resulting in a painful phenomenon known as “stagflation”. Five decades later, stagflation is today once again occupying the center stage in media and policy debates, as central banks, governments, economists and investors across global financial markets ponder the various potential scenarios that could lead to a repetition of the dreaded 1970s.

Fears of a stagflationary shock are being stoked by a “perfect storm” of sorts, comprising soaring inflation, decelerating economic growth and a spike in unemployment, that has engulfed the world in 2022.

Inflation surges

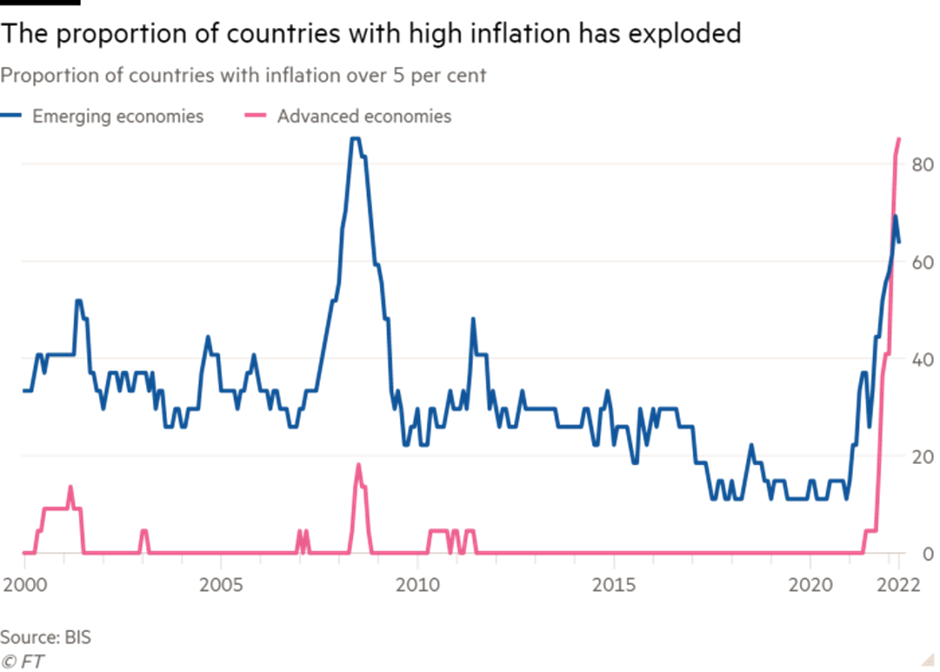

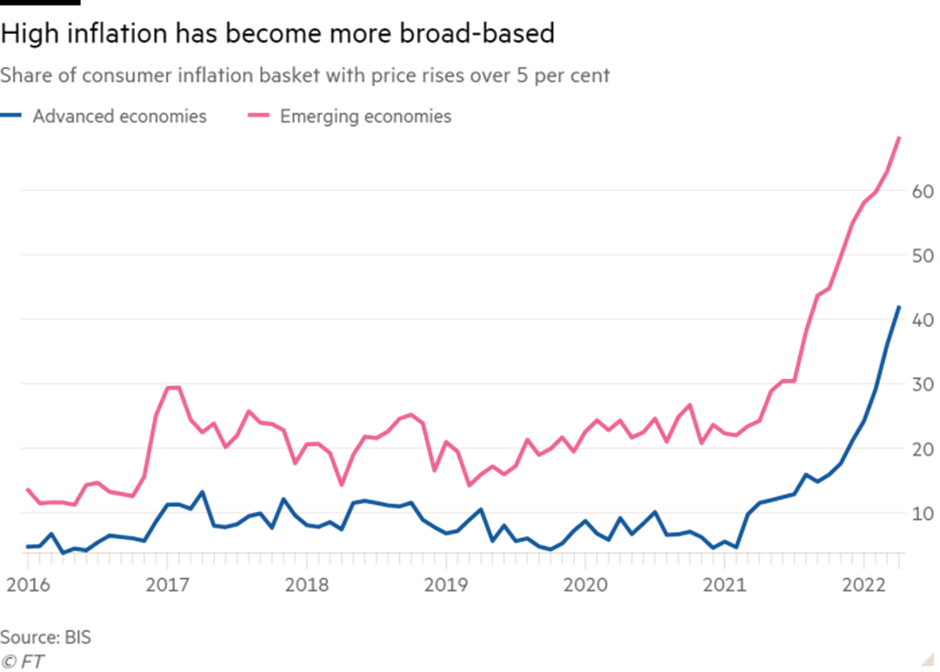

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February, consumer prices had hit multi-decade highs in the U.S., U.K., eurozone and several other countries. The inflation spike in 2021 was primarily thanks to the supply chain shocks induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and a massive jump in demand for goods and services resulting from huge fiscal stimulus programs and loose monetary policies.

The Russia-Ukraine geopolitical conflict exacerbated the inflation problem by setting off further supply shocks in the form of shortages in various key commodities such as natural gas, oil, wheat and fertilizers. This “commodities shock”, arguably the biggest of its kind since the 1970s, has sent food and energy prices further higher, in turn stoking inflation further – beside depressing spending and output.

As a result, inflation has now reached levels not seen in several decades in several economies. U.S. consumer prices increased1 to a new 40-year high of 8.6% in May, while living costs in the U.K. have jumped 9.1%2 on a year-on-year basis – representing the most rapid pace of acceleration in 40 years. Meanwhile, eurozone inflation rose3 to a record high of 7.5% in the first three months of this year, implying the hottest pace of price increase since the creation of the euro in 1999.

Slowing economic growth

In tandem, the outlook for global economic growth, which had rebounded in 2021 amid a post-pandemic recovery, looks increasingly bleak. In its recently published Global Economic Prospects report4, the World Bank sharply revised downward its estimate for worldwide GDP growth in 2022, to 2.9%, as compared to 5.7% in 2021. Record inflation, amid inadequate supply of core commodities, suggests “it’s going to be very hard” for some countries to avoid recession, World Bank chief David Malpass has warned5, adding that it would take “maybe two years to bring inflation back down”.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also downgraded3 its projection for 2022 economic expansion for 143 economies that represent 86% of global GDP. A U.S. recession was “certainly a possibility6,” Fed chair Jay Powell conceded on June 22, admitting that curbing inflation while preserving growth “is going to be very challenging.”

Meanwhile, China, the world’s second-biggest economy, is also slowing significantly, with official data for April showing a dramatic decline in consumer and business activity amid Beijing’s strict “zero covid” policy of imposing lockdowns. Japan, the world’s third-largest economy, contracted in the first quarter, while GDP growth in the eurozone slowed3 to a paltry 0.2% for the given period.

Policy dilemma: Growth vs price stability

Policy makers in both monetary and fiscal spheres today face a major dilemma – whether to prioritize controlling inflation, or to focus on averting a “hard landing” for the economy that induces recession. And it increasingly looks like central banks and lawmakers will have to make trade-offs in terms of which problem to address first.

If the current signals from policy makers are anything to go by, it is apparent that ensuring price stability is firmly on the top of their agenda even if that means reduced demand and employment. This represents a remarkable change in policy setting from 2021, when most central banks were convinced that then high levels of inflation were “transitory”.

Looking ahead

The stagflationary shock of 2022 is undoubtedly global in nature and scope, and not confined to a specific geography or economy. Across countries, a similar trend is panning out – an unanticipated spike in consumer prices, a sharp deterioration in economic activity over the past few months, and a worsening outlook for the rest of the year.

Are we looking at a protracted period of stagnation and inflation a la 1970s? The jury is still out on that one. A lot will depend on how successfully, if at all, the Fed manages to avoid a “hard landing” or “accidents” in financial markets and the U.S. economy as it keeps increasing interest rates and unwinding its bond-buying program.

Also, the risk of inflation getting more entrenched could get bigger if the historically tight labor markets in the US and Europe persist, leading to wage-price spirals.