The New Financial Supermarket: Evolution of Private Equity

April 29, 2022

When Henry Kravis and his cousin, George Roberts, quit Bear Stearns’ corporate finance unit alongside their mentor Jerry Kohlberg to launch Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR) in 1976, they would hardly have imagined they were giving birth to modern private equity.

The boutique investment vehicle, which focused exclusively on leveraged buyouts (LBOs) or “bootstrap” investments as they were called then, struck its first significant deal in 1979, acquiring auto components manufacturer Houdaille1 Industries for $355m.

Since then, private equity (PE) has grown, transformed, and evolved over these 46 years into a giant asset class worth $6.3 trillion2, diversifying beyond LBOs into other investment strategies such as private credit, real estate and insurance.

Spectacular growth…

The PE industry has tripled3 its assets under management (AuM) over the past decade, overseeing a capital pool today that is over four times2 what it managed at the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007.

And the profile of limited partners (LPs) in PE vehicles has undergone a noteworthy transformation as well, growing beyond the traditional pool of insurers, endowments, pensions and sovereign wealth funds to high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth individuals, and family offices, among others.

With such massive amounts of capital to deploy, buyout funds invested4 a record-breaking $1.036 trillion in new transactions in 2021, representing a 50% surge from the preceding year, as per the American Investment Council. And yet, the industry is sitting on so-called dry powder, or unspent capital, worth $2.5 trillion5.

… driven by outperformance

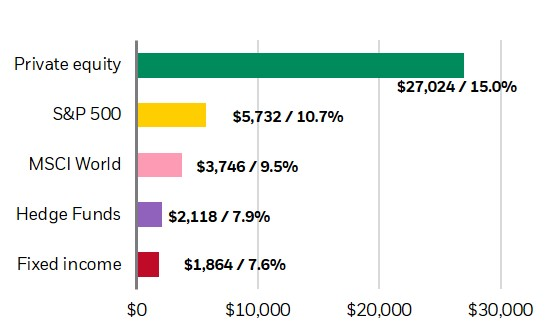

The stunning boom in private equity has been driven by significant outperformance as compared to other investment strategies. From 1980 to 2020, PE, as an asset class, generated annual time-weighted return of 15%, implying an alpha6 of 4.3% and 5.5% over the S&P 500 and MSCI World indices, respectively.

A hypothetical investment of $100 invested in five different financial instruments on 1 January 1980 and assuming reinvestment of all proceeds (Source: BlackRock)

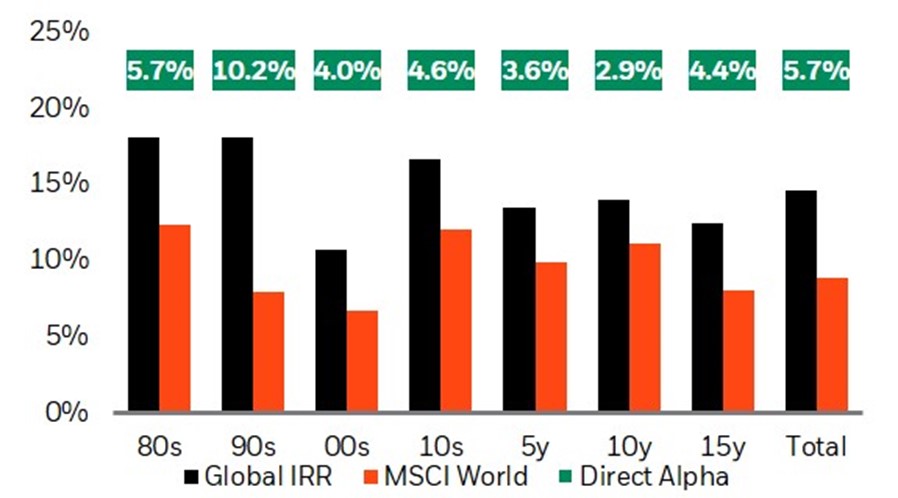

PE’s consistent outperformance over public markets during the last four decades is further highlighted by the following figure, which demonstrates strong returns on both relative (direct alpha) and absolute (IRR) basis.

Global private equity fund pooled, absolute and relative performance against the MSCI World index for 40 vintage years and 4 pooled aggregates – all in USD as of 31 December 2019 (Source: BlackRock)

The new conglomerates

The irony in this spectacular growth of private equity, however, is that many of the industry’s leading lights have today become corporate behemoths, increasingly resembling the traditional, sprawling conglomerates they themselves broke up in the 1980s.

The days of PE being a niche asset class, pertaining almost exclusively to aggressive LBOs underpinned by financial engineering via massive debt and huge cost-cutting, sound like distant memory now.

Marquee names in the industry today are financial supermarkets in many ways, owning pretty much everything: media and entertainment, real estate, infrastructure, pharmaceuticals, financial services, telecom, IT, and much more. So much so that earlier this year, Blackstone, the largest PE firm in terms of AuM, set itself2 an ambitious target of boosting its assets to $1 trillion by the end of 2022 – four years ahead of an earlier goal.

Rapid metamorphosis post GFC

If one were to identify major catalysts that changed the course of private equity in the last 20 years, and fueled its meteoric rise, the 2008 global financial crisis stands out as the defining one.

Since then, a large-scale retrenchment by banks from the credit landscape, amid imposition of tougher capital requirements, created a vacuum that PE firms opportunistically swooped on. Over the last 14 years, many buyout funds morphed into providers of direct lending and structured credit, beside acquiring non-performing bank loans, etc., effectively becoming “shadow banks”.

Industry titans like Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle Group and Apollo Global Management transformed themselves into diversified “alternative asset managers or platforms”, straddling multiple segments of private and public capital markets.

This mega structural shift has meant private equity is no longer confined to raising “blind pools” of capital for pursuing LBOs. Rather, industry players are now operating life insurance businesses to sell retirement products such as annuities; providing loans to big and medium corporations; provisioning credit to aircraft and mortgages, and snapping up income-producing real estate to became landlords.

That’s not all. Several PE firms are now aggressively getting into so-called “growth equity”, taking stakes in rapidly expanding companies, with a view to selling them later a much higher multiple.

The other major driver of the PE landscape transformation in the post-GFC era has been the prevalence of record-low interest rates and quantitative easing for over a decade. This dynamic has forced several institutional investors, who earlier were averse to investing in the asset class, to embrace buyout funds in the quest for risk-adjusted returns.

Conclusion

Hardly anyone, least of all the three musketeers who launched KKR and pioneered private equity as we know it today, could have predicted this journey for the industry thus far. While the first two decades saw PE establish itself as a differentiating asset class that delivers superior returns on capital as compared to public markets, the last two decades have seen the category morphing into an alternative asset management play.

For those bullish on the asset class, the fact that PE still constitutes “only a small fraction3 of total global equity markets”, should provide grounds for continued optimism in the value proposition of private equity.

And as the world gradually adjusts itself to the reality of high inflation, and in turn, higher interest rates and no QE, the financial supermarket that is private equity, could be well-positioned to distinguish itself once again and deliver uncorrelated returns.