What’s driving the 2022 sell-off in emerging markets debt?

June 30, 2022

When the U.S. sneezes, the world catches a cold, they say. No one knows that better than emerging markets (EMs). This asset class, which has been around since the late 1980s, comprises a wide and varied array of developing economies and companies, and has often delivered superior returns as compared to their relatively sober counterparts in the advanced world.

However, EMs have typically been an extremely volatile asset class, often impacted by the monetary policy actions of the U.S. Federal Reserve and major moves in global financial markets – including equities, bonds and foreign exchange (FX). The 2013 Taper Tantrum was a classic example of this dynamic, when the specter of the U.S. central bank gradually unwinding its post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) quantitative easing (QE) program triggered a broad-based sell-off in EMs, including bonds issued by sovereigns and corporates in developing nations.

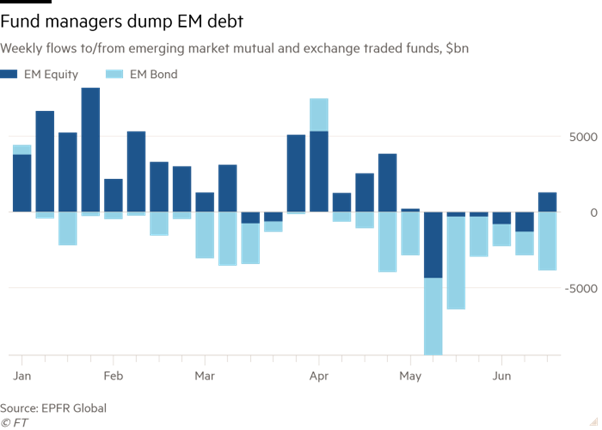

Cut to 2022, and we are witnessing a similar story unfold – and, at a far bigger scale. With the Fed increasing interest rates to cool raging U.S. inflation, and vowing to stay on that path till it ensures price stability – one of its dual mandates – investors are increasingly taking flight from EM bonds. Redemptions from EM debt-focused exchange traded funds (ETFs) and mutual funds have already crossed1 $40bn so far this year, according to data provider EPFR Global.

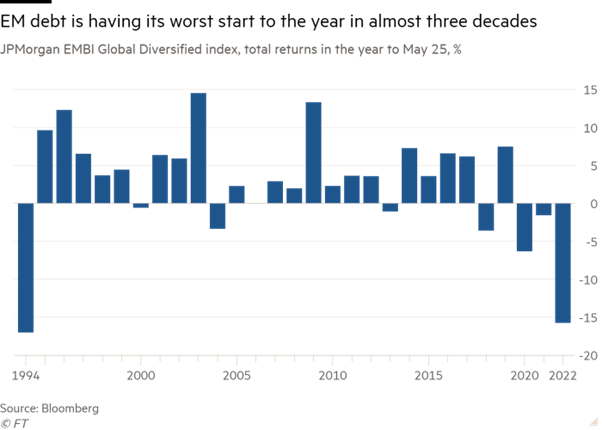

This wave of outflows has had a concomitant impact on the performance of emerging market fixed income, which is in the throes of suffering its worst losses in nearly three decades. As of April 28, 2022, the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversifed (EMBI GD), a benchmark index for US dollar-denominated EM sovereign bonds, had lost2 14.53% – its worst beginning to the year since 1994.

Tightening financial conditions amid yield differentials

The 2022 rout in EM bonds is pretty much along the lines of the cascading effects of global monetary tightening cycles in the past. Capital is pursuing higher yields in the U.S. now, with benchmark interest rates there going up substantially and likely to increase further in the coming months – thereby making EM bonds less attractive. For instance, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond – the benchmark “risk free” asset – yielded almost 0.75 % a year ago. Today, it is yielding over 3%, more than a Chinese 10-year sovereign bond.

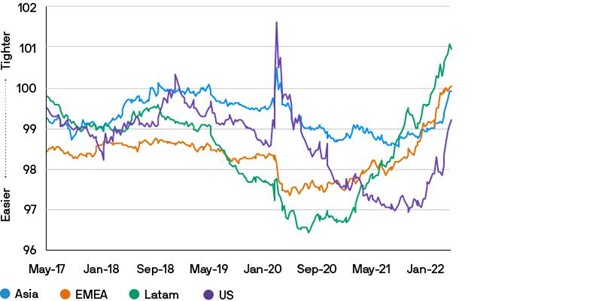

With financial conditions in the U.S. and rest of the world tightening rapidly, and central banks in the U.K, Europe and elsewhere following the Fed’s increasingly “hawkish” playbook, EMs are finding the going tough in terms of both access to capital and the cost of capital.

Emerging Markets Financial Conditions Index

Source: Bloomberg, J.P. Morgan Asset Management; data as of 26 May 2022.

Reduced liquidity

Another major driver of the ongoing sell-off in EM bonds is the deteriorating level of liquidity in global financial markets since the beginning of 2022. This aspect is noteworthy, given that the performance of EM assets has historically been significantly influenced by the quantum of capital seeking investments.

For over a decade, developing economies enjoyed huge amounts of liquidity since the 2008-09 GFC, thanks to the ultra-accommodative monetary policy adopted by the Fed and its counterparts in the developed world, including in the aftermath of the 2020 COVID pandemic. Zero-bound interest rates, combined with multi-trillion dollar QE in the form of bond-buying programs, drove massive capital inflows into EM bonds during this period.

That era is coming to an end now. The Fed’s unwinding of that unprecedented stimulus, in the form of rate hikes and a phased quantitative tightening (QT) via sales of various securities it purchased during QE, signifies a “regime change”, with major implications for liquidity. While the Fed officially began QT in June, some market participants believe it began discreetly pulling liquidity from U.S. money markets way back in December 2021. In fact, the Fed’s QT program has already amounted to a net $1 trillion1 , over 10% of its balance sheet, according to estimates.

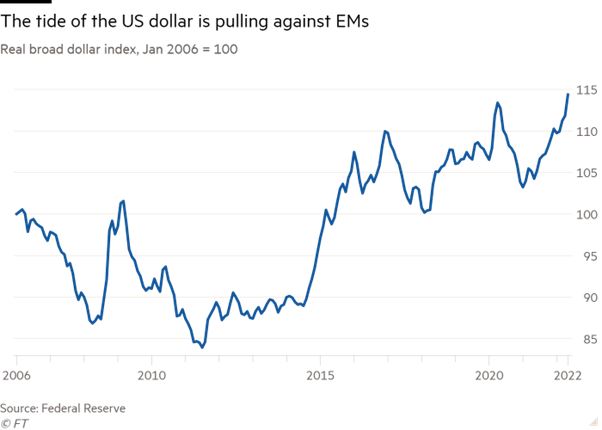

Dollar exchange rate

It’s not only yield differentials and reduced liquidity that are behind the carnage in emerging markets bonds this year. The dollar exchange rate is also playing a big role. The Fed’s index of the greenback’s value against a basket of 26 currencies, which declined for about 12 months from its most recent high during the onset of the pandemic, has since rebounded, hitting a new record high in May.

The dollar’s sharp appreciation is a big concern for many developing countries, whose companies and governments have borrowed huge amounts in foreign currencies, and done so at floating rates. The World Bank cautioned recently about external public debt in EMs hitting record levels, noting that “debt distress – previously confined to low-income countries – is spreading to middle-income countries”.

Looking ahead

The outlook for emerging markets debt remains challenging over the near to medium term, as the risk of stagnant or slowing economic growth worldwide – including in U.S, eurozone and China – rises. What could compound the misery further is the possibility of heightened geopolitical conflicts including Russia’s war in Ukraine, which could adversely impact already skyrocketing commodities prices.