Eurozone sovereign debt woes: 2012 redux in store?

July 29, 2022

“Whatever it takes” – inarguably among the most powerful words uttered ever by a central banker. Yes, we are talking about the momentous speech1 delivered in London on July 26, 2012 at the peak of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis by then European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, who vowed to “do whatever it takes”, within the institution’s mandate, to “preserve the euro”. He added, “believe me, it will be enough”.

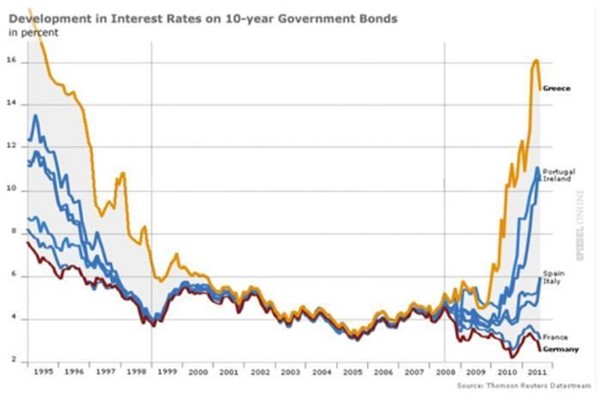

Draghi’s comments came against a dire backdrop. Yields on sovereign debt issued by the so-called “PIIGS” group of peripheral eurozone member nations – comprising Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain – had hit historic high (as illustrated by chart 1), with investors demanding a steep premium to finance their economic bailout programs.

The “spread” between distressed peripheral eurozone sovereign bonds and the benchmark German “Bunds” was hovering at dangerously high levels, in turn triggering a massive depreciation in the euro and casting a serious question mark over the single-currency union’s survival.

Well, Draghi’s speech changed the course of history. Sovereign spreads in the euro area plummeted after his verbal intervention. In fact, his firm commitment to protect the euro and eurozone monetary union proved adequate in bringing down eurozone bond yields and restoring investor faith in struggling “PIIGS” countries.

Divergent sovereign borrowing costs

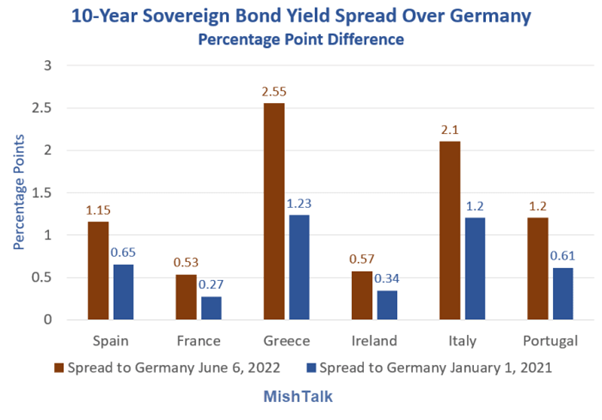

Cut to July 2022, and the eurozone today is again staring at a potential replay of the crisis it was engulfed with a decade ago. The differential between yields on government debt of a group of “vulnerable” peripheral eurozone member states and those on Bunds has widened significantly recently.

Italy was recently forced to pay2 the highest borrowing costs on its debt since the 2012 eurozone debt crisis. Rome issued five- and 10-year bonds worth a combined €6bn on June 30 at yields of 2.74% and 3.47% respectively, having last auctioned equivalent medium- and long-term paper at higher yields in 2013 and 2014. Similarly, the spread3 on 10-year Greek and Spanish sovereign bonds hit almost 262 basis points and 126 basis points, respectively, on June 15.

Concern over debt-to-GDP ratios

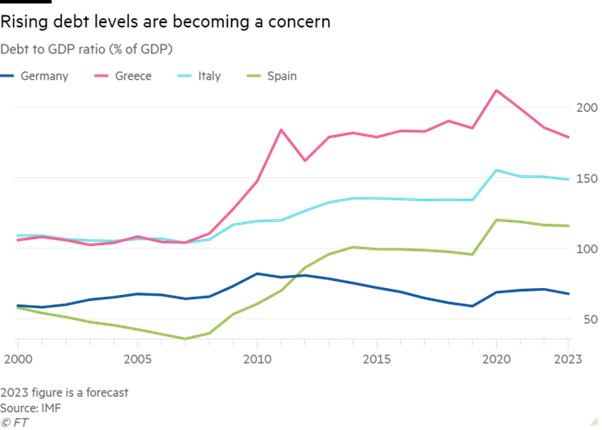

The principal driver of the widening spread in 10-year bond rates across peripheral Europe relative to Germany has been the onerously high levels of public debt in the eurozone. Indebted countries such as Spain, Greece and Italy had been on a borrowing binge since the resolution of the region’s sovereign debt crisis a decade ago, capitalizing on ultra-low interest rates available then amid a super-accommodative global monetary policy paradigm. This dynamic got further reinforced by the ECB’s mega bond-buying program.

However, with eurozone inflation hitting a two-decade high4 of 8.6% in the year to June – over four times the central bank’s 2% target – that scheme of things has changed dramatically in 2022. On July 21, ECB president Christine Lagarde unveiled5 the institution’s first rate hike since 2011 by announcing a 50-basis point increase, and vowing to “deliver” on price stability across the single-currency bloc. The move, which marked an end to the ECB’s eight-year-running negative rates program – was accompanied by a guidance that monetary tightening would likely continue going forward as “upside risks” to inflation persist.

Bond markets have since taken cue, with government borrowing costs soaring3 throughout the 19-country currency bloc’s periphery. Yields on sovereign debt issued by southern European nations are once again spiking in the wake of the ECB’s resolve to unwind quantitative easing.

Political instability

Compounding matters is the current political turmoil in Rome, where prime minister Draghi resigned on July 21 after the three biggest political parties in the country’s national coalition unity government boycotted a confidence vote – triggering the dissolution of parliament and pushing Italy into snap elections on September 25.

Draghi’s exit comes at a crucial juncture for both Italy and the eurozone, which are battling huge economic challenges including a deceleration in business activity and a plunge in consumer confidence, and soaring food and energy prices in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The ex-Italian premier had planned structural economic reforms to boost Italy’s appeal as an investment destination, and to assure investors regarding the sustainability of Rome’s public debt that currently equates to about 150%6 of gross domestic product. However, the country’s political crisis has cast a shadow over that plan, with investors questioning how rising rates will impact Italy’s ability to service its debt.

Looking ahead

Are we looking at a sequel to 2012 here? The jury is still out on that. One thing is clear, though – as peripheral risk premia across the eurozone increase once again after a multi-year hiatus, and the ECB embarks on tightening monetary conditions to tackle2 inflation in “a determined and sustained manner”, indebted peripheral member states will find the going increasingly tough.