The Geopolitical Chessboard: Navigating Volatility in Energy and Food Commodities

January 27, 2026

As 2026 unfolds, the global commodity markets are operating under a “caffeine shot” of volatility. Despite global growth rate of 2.6 % to 2.8% projected for the year, an increasingly complex and volatile geopolitical flux is set to severely test this growth rate. the record-breaking surge in precious metals to the restructuring of energy flows for the AI boom, interspersed with an impending unlocking of the JPY carry trade, the “uncertainty premium” has become a primary driver of market valuations.

The Shifting Risk Premium

The beginning of 2026 has been marked by what analysts describe as “Macro Mania.” The visible indicator of this geopolitical tension is the historic rise in safe-haven assets. Silver recently smashed through $90 per troy ounce, while Gold peaked at $4,650, driven largely by regional developments and shifting diplomatic alliances across the Middle East and South America.

Gold and Silver Price Movements Jan-Dec 2025

These price movements reflect a shifting “geopolitical risk premium.” In the energy sector, market participants are moving beyond simply pricing in standard supply and demand; sudden administrative shifts, driven by political realignments and trade bloc recalibrations, are ushering in an era of heightened unpredictability in which commodities function as the “ultimate reserve currency” for a world navigating rapid political change.

This premium is especially evident in the oil and gas sectors, where the possibility of restricted transit or altered export quotas keeps prices in a state of perpetual flux. Geopolitical shocks generally increase commodity return volatility, particularly for energy products such as crude oil and natural gas, because of their central role in global trade and production networks.

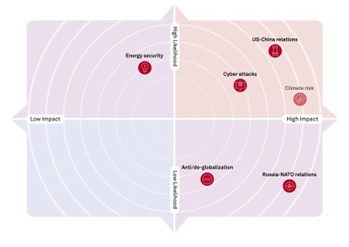

Likelihood and Impact of Top Geopolitical Risks

In addition to the above risks, which were outlined as the key risks of 2025, the emerging US-NATO conflict over Greenland is a new risk that will decisively impact Eurozone growth in 2026 and, indirectly, the rest of the world.

The “Fracturing” of Global Markets

The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report (January 2026)3warns that while the global economy is resilient, it is also “fracturing.” With trade and tariff-driven disruptions increasingly used as a tool of statecraft, this fracture is most evident in the trade of food and essential commodities, leading to significant supply-side shocks.

The World Bank notes that 25% of developing countries still have lower per capita incomes than in 2019, primarily because they lack fiscal cushions to absorb volatility caused by international trade barriers. In Europe, the Eurozone’s growth is expected to remain modest at 0.9% to 1.3%, partly due to the drag from new tariffs and high energy costs. These “regulatory walls” force a recalibration of global food routes, often leaving regions that compete intensively for resources to face higher prices and lower availability.

The Weaponization of Exports and the “Data Center” Dilemma

A unique feature of the 2026 landscape is the need to balance energy demand between traditional industrial needs, the digital frontier, and population needs. This has led to economies creating new policy imperatives, such as the most recent requirement that tech giants “pay their own way.” President Trump recently asserted that the AI data center boom must not cause households to “pick up the tab” for power consumption. Having said that, such rebalancing will have ripple effects:

- Supply Diversion: Energy that might have been destined for the global export market or the general grid is being redirected to domestic high-tech infrastructure.

- Infrastructure Bottlenecks: As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella recently observed, the bottleneck for AI is no longer a shortage of chips, but a shortage of “warm shelves” close to power sources.4

- Cost Inflation: With average electricity costs up approximately 40% since 20215, the push for tech firms to fund their own power, often through private nuclear pacts, aims to insulate the public from the energy demands of the digital arms race.

The Weaponization of Energy and Food Exports

For decades, nations have used export restrictions, tariffs, and sanctions to pursue economic and policy objectives. Such measures, while focused on achieving strategic ends, can inadvertently limit the availability of key commodities on international markets.

For example, export restrictions on agricultural products or raw materials reduce the effective supply accessible to international buyers, tightening global markets and driving price spikes. Restrictions on fertilizer exports – or limitations on key agricultural inputs – have historically constrained production capacity in importing countries, amplifying price pressures.

Energy markets are similarly affected. Sanctions on production or export infrastructure disrupt long-established trading flows. By limiting market access for certain supplies, these policies shrink total available volumes and cause buyers to seek alternative (and often more expensive) sources. These adjustments can happen quickly, pushing prices higher or causing greater volatility, as markets recalibrate expected supply paths.

The result of such selective restrictions is not only higher prices but also greater uncertainty about future supplies, which markets respond to by incorporating larger risk premiums into commodity forward and futures prices.

The Hedge Fund Response: Chaos into Cash

For institutional investors, this volatility is not a deterrent but a catalyst for performance. Hedge funds recorded their best gains in 16 years in 20256, with an average return of 12.6%. Many firms have thrived by navigating the “chaos” of shifting geopolitical and macroeconomic trends.

Hedge fund managers are increasingly employing multi-strategy models to play commodity spreads. They are focusing on:

- Arbitrage Opportunities: Exploiting price differences between regions caused by trade restrictions and sanctions.

- Strategic Hedges: Using precious metals and “Carbon 2.0” markets to protect against fluctuations in the U.S. dollar, especially as the Federal Reserve prepares for a leadership transition following Jerome Powell’s scheduled exit in May 2026.

A Delicate Balancing Act

The geopolitical chessboard of 2026 is defined by a “trilemma”: the need to fuel a technological boom, the requirement to maintain stable food and energy prices for households, and the reality of ongoing regional transitions. As the Bank of Japan signals potential rate hikes for April 2026 and the U.S. Federal Reserve enters a period of political turmoil, the independence of monetary and energy policy remains under pressure. In this environment, the risk premium is no longer a temporary spike; it is a structural component of the modern commodity market.

Sources:

1. https://www.cnbc.com/2026/01/14/silver-gold-price-record-100-5000-export-us-china.html

2. https://www.spglobal.com/en/research-insights/market-insights/geopolitical-risk

4. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/microsoft-ceo-satya-nadella-admits-143026640.html

5. https://powerlines.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/PowerLines_Utility-Bills-Are-Rising_2025-1.pdf

6. https://ca.finance.yahoo.com/news/hedge-funds-post-biggest-annual-115810950.html