UK’s Mini Budget and It’s Massive Fallout

October 31, 2022

No pain, no gain is a common refrain from the political class when they accept that someone goofed. The mini-budget chaperoned by British Prime Minister Liz Truss and her Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng was meant to fill a £60 million blackhole in government finances, but it left an economy damned for the immediate future. Rising borrowing costs, crippled energy bills, high taxes and no clear path around growth revival is what Britain is left struggling with. Both the key actors in this theater of the absurd have lost their jobs and most of what the mini-budget brought has also been reversed in the interregnum.

The mini-budget and its impact

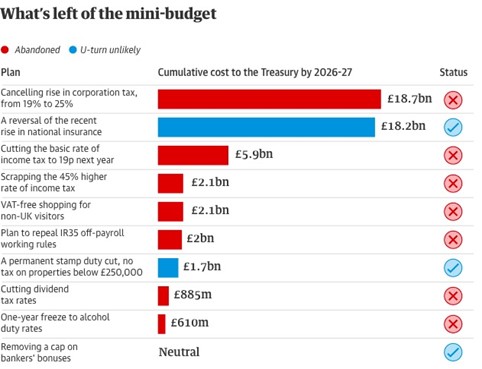

Prime Minister Truss described it as the Growth Plan designed to boost economic growth via tax cuts to be paid for through a sharp increase in UK national debt. The plan was ambitious to say the least – it was worth £161 billion over five years with another £60 billion apportioned for the 2022-23 energy bills support package – and would have been the biggest tax cut in the UK since the 1972 “dash for growth from Anthony Barber. Some of the measures included:

- Basic income tax rate was to be cut to 19% from April 2023, which was said to help 31 million people about £170 a year.

- Abolished the 45% rate of income tax for savings over £150,000 for taxpayers with a single higher rate of income tax of 40% being levied from April 2023.

- Removed country-wide rise in corporation tax that was due to go up from 19% to 25% from April of 2023.

- Energy subsidy for typical households using both gas and electricity amounting to £2500 annually for two years

The irony is that most of these announcements were rescinded by Jeremy Hunt, who replaced Kwarteng as the Chancellor. Hunt said he was scrapping almost all the tax cuts announced in September that signaled public spending cuts. Besides the tax cuts, he also scaled back a cap on energy prices, all of it possibly aimed at restoring market confidence. The Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget missed the one crucial bit of information that every market seeks – how will any proposed tax cut be funded? In the absence of this data, the Pound plummeted, cost of government borrowings soared and the Bank of England was forced into a firefight by purchasing government bonds to prevent a further spread of the financial crisis.

The writing was very much on the wall

Some political pundits perceived the appointment of Hunt as a complete reversal for all that Truss had campaigned for, because he had served two of Truss’s predecessors Theresa May and David Cameron. Hunt was also known to be a leading supporter of her Conservative Party rival for Number 10 and former Chancellor – Rishi Sunak – who eloquently described the efforts as “fantasy island economics” where revenue sources are removed without filling up that fiscal hole that such give-aways create. It has also been criticized for ignoring the runaway inflation trends compounded by the Ukraine crisis and energy market convulsions. In fact, the Truss-Kwarteng proposals on abolishing a 45% income tax rate and scrapping a hike in corporate taxes, which together accounted for £45 billion in unfunded tax cuts, saw yields on 10-year government bonds jumping from 3.5% to 4.3%, before the Bank of England pumped in £65 billion to stabilize the market.

What needs to be done – right here, right now?

The U-turn on tax cuts have temporarily ameliorated the turmoil but there are deeper changes at the macroeconomic levels that need to be put in place to bring the UK back on a stable path of economic growth and manageable inflation levels. The executive also needs to support the Bank of England’s attempts to handle inflation, which stands at around 13% which has followed the Fed and hiked interest rates to moderate business and consumer spending. A third area of focus needs to be around creating a robust public investment program, for which they needn’t look beyond the trillion-dollar climate and digitization scheme proposed by the EU, unless they would rather borrow from the US climate and infrastructure program.

On his part, the Chancellor has warned of some “difficult decisions” stating that some areas of spending would need to be cut. Most of the focus is likely to remain on whether state pensions and benefits are increased next year in line with September’s inflation rate and on public sector pay and day-to-day spending options. Some economists expect cuts worth several tens of billions of pounds if the government aims to meet its public finances target of national debt falling as a percentage of GDP. Others believe he may choose to reduce long-term investment spending, which could be at the cost of longer-run growth and public service capacity. At this point, it is tough to see which of the government’s big chunks of spending – health, pensions, welfare, education and defense – could face the Chancellor’s scythe.

As we write this blog, comes the news that former Chancellor Rishi Sunak is set to take over Number 10. Let’s wait and see how this self-proclaimed “proud Hindu” brings the British economy back from fantasyland to reality without getting caught up in what the world once knew as the Hindu rate of growth.